Hotel gyms seem be improving! This is from the Marriott Waterfront in Baltimore.

On August 16th, 2010, I tore my right anterior cruciate ligament (the main ligament in the knee) at a fight training class. This is part 1 of the story of how it happened, the reconstructive surgery, the 5 months of physical therapy that followed the surgery, and my gradual return to full participation in fight training.

The Injury

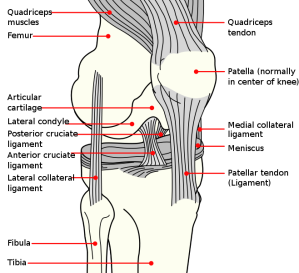

The ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) is the most important of the four ligaments which stabilise your knee. It’s is a strip of connective tissue which inserts at the front of the bony plateau at the top of your tibia (in your lower leg) and crosses to the back of the distal part of the femur (in your upper leg.) Its major functions are to resist your lower leg being drawn forward and/or twisted in relation to your upper leg.

The other three ligaments in the knee are the PCL (posterior cruciate ligament) which, by contrast, inserts towards the back of the tibial plateau and runs forward to the front part of the femur. It forms a cross with the ACL, hence the name “cruciate” and the “anterior/posterior” part comes from where the ligament attaches to the \emph{tibia} (not the femur.) (The other two ligaments are the LCL, or Lateral Collateral Ligament (on the outside of the knee) and MCL or Medial Collateral Ligament (on the inside of the knee.)

ACL tears are common sports injuries, especially in sports that involve a lot of darting, landing, or changing direction, such as football (both the American and soccer varieties) and basketball. One man I met at physical therapy had torn an ACL on five separate occasions (getting it reconstructed in between, of course, he only had the two legs.) Women are more likely to tear an ACL than men, but at the time it happened to me, the only ACL tearing incident I’d heard about was that of the male English footballing legend Michael Owen, who tore his ACL in 2006 World Cup against Sweden. You can actually watch him do it here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LoFimQmMrbM You’ll see that Owen isn’t touching anyone, or kicking the ball at the time. Non-contact tears like this are very common; you don’t need to be tackled or kicked to tear an ACL.

Unlike many, mine was not a non-contact tear. I was doing stand-up randori with a friend at my martial arts class. We were the only two people in the class at the time, so our instructor, Robert Miller, was watching us closely. We were outside on grass, and wearing athletic shoes. My friend is a fair bit bigger than I am, so was really putting my all into my attempts to throw him. I was feeling pretty good, because I’d just managed to get an seoinage throw to work. We were in the last few seconds of the round and I managed to line everything up for a good osotogari leg sweep with my right leg. I didn’t get it cleanly and he didn’t go down right away. So I did what you do to force it: I planted my sweeping leg, and attempted to use every atom in my body to force him back over it. He bore down to resist. I pushed hard…but instead of him going back, there was a pop from my right knee and I found myself on the ground, yelling and clutching my knee, with a very worried looking practice partner looking down at me and wondering what the hell had happened.

The intense pain didn’t last long, and within two minutes I was able to get to my feet and limp away. (We finished the class there.) The back of my calf felt tight at the top, near my knee (I now know that was because when your ACL isn’t there to resist anterior draw of the tibia relative to the femur, your gastroc muscle tries to do that job instead. The tightness was my gastroc freaking out at all the new work it was going to have to do.) But I was ok, I thought, I’d just strained my knee or my calf in some way, and a little ice and elevation would have me fixed up in a couple of days. Deep down I knew that the popping sound I’d heard was a bad sign—that people reported hearing such noises when their ACLs went—but, honestly, I thought I was ok—it just didn’t hurt that much any more. Anyway, I iced, I elevated. I walked funny. But I didn’t think I I’d done anything that wouldn’t heal itself in couple of days. More fool me.

The next night I was teaching karate at Washington University. I was demonstrating a technique, shifting forward in stance to block before grabbing and pulling someone into your punch. And as I shifted forwards there was another crack from my forward knee—this time it felt like the noise was from the femur slipping against the tibia—and I found myself back on the ground, with more yelling, this time with a few more alarmed people looking down at me. Everyone had heard the crack. And my knee had just collapsed on me.

Diagnosis

That collapse was surprising and unexpected enough that I called my GP the next morning. Robert Miller came with me when I went to see her. She asked me what had happened and performed a few tests for knee stability, including one with which I am now very familiar— the Lachman test—the standard clinical test for ACL function. Then she said: “I’m not totally sure, but going from what you’ve said, the way you are holding your leg when you stand, and from manipulating it, I think you might have torn your ACL. Anyway, I’m going to send you to an orthopedist, so we can find out for sure.”

And honestly, I thought—naah. What does she know? She’s just a GP. My leg is probably fine. I’ll go and see the orthopedist and they’ll tell me it’s just a strain. (Looking back I find it easy to recognise the element of denial— a commonly reported response in the sports psychology literature—in my own process.) So I went to see the orthopedist. He repeated the Lachman test, immediately diagnosed an ACL tear and scheduled me for an MRI to try to find out what other damage I might have done. He also gave me a brace for my leg, to try to minimise any extra damage I might to the soft tissues until we figured out just how stable my leg was (at this point there was some question about whether I might have damaged the LCL at the same time as the ACL.)

One of the sad things about the injury and brace was that it took me out of FSRI's 2010 demo at the MoBot Japanese Festival. Here I am mic-ed up to present, with Chris looking sad about lacking a partner to demonstrate with.

As it turned out, I only had to wear the brace for a week, but that week was miserable. You wouldn’t think it would be such a big deal—the brace only weighs a few pounds and since I was injured anyway, it’s not as if I was walking normally before I started wearing it. So let me break down the ways in which wearing it was bad. First, it locked my leg in extension, making it impossible to bend my knee. I couldn’t ride my bike, and I couldn’t walk normally—a major disruption to my lifestyle, though since classes hadn’t yet started at the University where I teach, I didn’t need to get to work each day, and so didn’t need to ride my bike as much. But you only have to go without bending your knee for a few hours to really, really develop a serious yen to bend your knee. When I took the brace off to shower I would attempt to bend it but the hours of extension had shortened the quadriceps around it to such a degree that bending it was slow torture. The additional weight of the brace puts extra strain on your hip flexors as you walk (you end up walking as if your braced leg was a pendulum—something you have to swing forward as one piece, like a crutch) tightening them on the side with the brace. This in turn puts extra pressure on your lower back, leading to much achey-ness. I also to sleep in the brace, which is not so easy, and meant that I was getting less sleep, and with it less recovery.

I haven’t mentioned the worst part yet, which is that in the week of wearing the brace the muscle melted off my right leg like warm butter. All those years of training and building up quad and hamstring strength disappeared in a few days, leaving my right leg about half the size of the left. It was this, I think, that really brought home to me that I had to take the injury seriously. I couldn’t look at my shrivelled right leg next to the as-yet still muscular left one in the mirror and not realise that something had gone very very wrong here.

The results of the MRI came back, confirming that I had a complete ACL tear, but no other serious problems (except that I was as incapable of lying completely still for 40 minutes as a 2 year old on Red Bull. Doctors from then on would frown and shake their heads over the “movement artefact” on my MRI.) I was allowed to take the brace off, and proscribed physical therapy for a few weeks while the inflammation from the initial injury went down, and while we considered options for surgery—the topic of a future instalment of this account.

The modern understanding of “the core” and the need to properly condition it has become well known among athletic and active people, including martial artists (yes, the importance of the hips has been belabored for centuries, but the modern anatomically based concept is not necessarily the same thing). The core refers to the muscles, connective tissues and bones of the torso, yet to many it’s just the rectus abdominis (the “6-pack’). However, the core can be more accurately thought of as the support, stabilization and movement system for the spinal column. This stack of 33 vertebrae (24 moving and 9 fixed) is connected by many ligaments and muscles, which provide oppositional tension akin to the guy wires on a tall tower.

As we continue to develop our programs and explore our group identity, it became apparent that we cover a lot more ground than the average “martial arts” school, and still have a lot of more to cover. Practical, eclectic fighting skills taught at the individual level, training priorities guided by analysis of violent situations and environments, instructional methods based on modern motor learning and educational models, an emphasis on accurate knowledge of human anatomy and psychology, supported by cutting edge performance enhancement and injury prevention conditioning, a commitment to honest and ethical practice…it’s not easy to get it all into one neat bite. As a part of my ongoing MS (Human Movement) coursework, I was recently required to develop a personal mission statement that reflects my goals in the field as well as a commitment to ethical and evidence-based practice. This got me wondering about what our group sees as it’s mission. After much discussion and exchanging ideas among the St. Louis, Wash U and Virginia clubs, the following reflections of who we are and what we do took shape:

1a. Our mission is to empower responsible adults through teaching them fighting and self defense skills.

b. We do not restrict our training to those who are already fit and strong: we aim to teach those who might need to fight, not just those who are naturally good athletes and fighters.

2a. We recognize that physical strength and fitness are an advantage in fighting and help to prevent injuries in training, and so an essential part of our mission is increasing the strength and fitness of the people we teach.

b. We hold that appropriate programming begins with the needs of the students.

c. We are aware of much misleading and false information about both fighting and fitness. We recognize the scientific method as the best means to sort truth from mere opinion and we are committed to reason-and evidence-based approaches. It is a part of our mission to update our beliefs and practices in response to new evidence.

d. Publication of quality evidence-based literature and original research, experiential knowledge of other fighting arts and the as well as organization of seminars and symposia, are a priority to which all members of FSRI are encouraged to contribute per their specialties.

3a. We endeavor to foster an atmosphere in which responsible adults may learn to fight regardless of class, race, gender, sexual-orientation, age or disability.

b. We are committed to creating a training environment that enables and encourages cooperative learning, and which promotes problem-solving as a means to forging healthy personal relationships as well as appropriate responses to violence

c. We reject any conflation of ability in fighting with moral rectitude. These things are distinct. Being a teacher of fighting does not make one morally superior to one’s students. Being a better fighter does not make one a better person.

This is a follow up to Bob’s introduction to rhabdomyolysis as it relates to martial artists.

Rhabdomyolysis is the destruction of skeletal muscle leading to the release of the muscular tissue components creatine kinease (CK) and myoglobin into the bloodstream (Huerta-Alardin, Varon & Marik, 2004). These components can pose a potential serious risk to the kidneys as they are cleared from the blood stream. Rhabdo can be caused by numerous factors, and can cause symptoms ranging in severity from mild to life threatening. Classic symtpoms include muscle pain, weakness and darkened urine (ranging from pinkto cola colored). Blood tests reveal elevated serum CK and myoglobin levels. More severe cases may present symptoms such as malaise, fever, tachycardia, nausea and vomiting (Huerta-Alardin et al., 2004). In severe cases acute renal failure can result, requiring medical attention.

One of the most disturbing aspects of the martial arts is the lack of adequate sports safety training among martial arts instructors. Deference to tradition regarding training methods and expectations of performance often blinds instructors to the intrinsic dangers associated with fight training. While it is probably impossible to ameliorate all of the dangers associated with fight training responsible instructors should make every effort to be aware of the symptoms of training related injuries, and related conditions.

Rhabdomylosis is potentially fatal condition coaches and trainers of all sorts should be aware of. It can be caused by excessive exercise, and other activities that traumatize skeletal muscle tissue like katakite, tanren, or even pummeling drills. When pounding and crushing activities are combined with intense physical activity the danger is probably greatest.

Here are a couple of links to articles of rhabdomylosys that may be useful for both instructors and trainees:

Wikipedia-Rhabdomylosys

Rhabdomyolysis ( /ræbdoʊmaɪoʊlɪsɪs/ or /ræbdoʊmaɪoʊlaɪsɪs/) is a condition in which damaged skeletal muscle (Ancient Greek: rhabdomyo-) tissue breaks down rapidly (Greek: –lysis). Breakdown products of damaged muscle cells are released into the bloodstream; some of these, such as the protein myoglobin, are harmful to the kidneys and may lead to kidney failure.

We were recently shocked to learn that that our martial arts colleague and friend in the UK, Mr Harry Cook, has been convicted of sexual assault. Whilst we are still struggling to process our personal feelings about the news, we would like to take this opportunity as an organisation to condemn these serious crimes and express our anguish for the victim and her family. Our thoughts are also with Harry’s wife and children, and with the others whose lives and relationships have been affected. The history of martial arts is littered with examples of people who used their mystique as a teacher to exploit their students – criminally or otherwise. Here at FSRI we’ve worked hard to create a culture in which things are different, and we liked to think that the teachers at clubs we associated with were different too. It is with deep anger and sadness that we realise we were wrong about this.

Recent Comments